‘I know the island well: I am not afraid of an army if it tries to find me at night.’

Island fiction, that specialised genre, exploits the novel’s innate artificiality. The relationship between setting and structure become so pronounced as to be almost indivisible. According to Raymond Chandler, any writer short of ideas about what to do with a story, should ‘have a man come through a door with a gun in his hand.’ It need not be a man, a gun or a door, but the effect would be the same: each new arrival offers the potential to divert the path of a narrative. This aspect is heightened by an island, where any visitor- even a footprint in the sand- is a significant event. Who is that approaching on the horizon? It’s the story…

Island fiction, that specialised genre, exploits the novel’s innate artificiality. The relationship between setting and structure become so pronounced as to be almost indivisible. According to Raymond Chandler, any writer short of ideas about what to do with a story, should ‘have a man come through a door with a gun in his hand.’ It need not be a man, a gun or a door, but the effect would be the same: each new arrival offers the potential to divert the path of a narrative. This aspect is heightened by an island, where any visitor- even a footprint in the sand- is a significant event. Who is that approaching on the horizon? It’s the story…

Written in 1940 by the Argentinian Adolfo Bioy Casares, The Invention of Morel crystallises the artificiality of the island genre. Born in 1914, Casares collaborated on a series of detective novels with Jorge Luis Borges who, in his prologue to the novel, described Morel as ‘perfect’ and made the following observation about this exercise in plot:

Written in 1940 by the Argentinian Adolfo Bioy Casares, The Invention of Morel crystallises the artificiality of the island genre. Born in 1914, Casares collaborated on a series of detective novels with Jorge Luis Borges who, in his prologue to the novel, described Morel as ‘perfect’ and made the following observation about this exercise in plot:

‘Detective stories… tell of mysterious events that are later explained and justified by reasonable facts… The odyssey of marvels [that Casares] unfolds seems to have no possible explanation other than hallucination or symbolism, and he uses a single fantastic but not supernatural postulate to decipher it.’

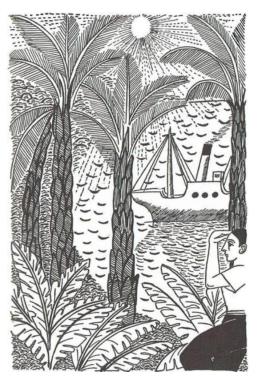

Influenced by The Island of Doctor Moreau, Robinson Crusoe and Casares’s fascination with Louise Brookes, the novel follows the story of a fugitive who washes ashore on a desert island and his  encounters with a group of mysterious tourists. At first, the narrator hides from them. Gradually, he becomes fascinated by one of the party, a woman who ‘sits on the rocks to watch the sunset every afternoon. She wears a bright scarf over her dark curls; she sits with her hands clasped on one knee; her skin is burnished by prenatal suns.’ He returns to the rocks every day, spying on the woman in a state of growing obsession. As he navigates the island and houses, he eavesdrops on the conversations amongst those present, including the inventor Morel. A sense of unreality begins to dominate; the narrative plays with its own artificiality. ‘So I was dead! The thought delighted me. I felt proud, I felt as though I were a character in a novel…’ Two suns hover over the island. The narrator announces himself to the party, only to be snubbed. What is happening encroaches on him steadily. He begins to doubt his own mental state, even guessing himself to be in a mental hospital only dreaming that he is on an island.

encounters with a group of mysterious tourists. At first, the narrator hides from them. Gradually, he becomes fascinated by one of the party, a woman who ‘sits on the rocks to watch the sunset every afternoon. She wears a bright scarf over her dark curls; she sits with her hands clasped on one knee; her skin is burnished by prenatal suns.’ He returns to the rocks every day, spying on the woman in a state of growing obsession. As he navigates the island and houses, he eavesdrops on the conversations amongst those present, including the inventor Morel. A sense of unreality begins to dominate; the narrative plays with its own artificiality. ‘So I was dead! The thought delighted me. I felt proud, I felt as though I were a character in a novel…’ Two suns hover over the island. The narrator announces himself to the party, only to be snubbed. What is happening encroaches on him steadily. He begins to doubt his own mental state, even guessing himself to be in a mental hospital only dreaming that he is on an island.

To describe Morel as science fiction probably gives the game away. Even for 1940, the book’s treatment of technology feels remarkable. Whereas Brave New World presents a technological civilization as horrific to its savage protagonist, in Morel, technology is portrayed as an inevitable extension of what it has always meant to be human. ”I feel the deepest respect for the men who first learned to kindle fires; how much more advanced they were than we!’

From the bone that crushed a tapir’s skull to the iPhone, humans have always surrounded themselves with technology, although such examples are only ever been tools, distinct objects. Morel examines what happens when that technology infiltrates our sense of reality. The book would be adapted into film in 1974, and has influenced Alain Resnais’s Last Year at Marienbad, and— along with Flann O’Brien’s The Third Policeman— also the TV series, Lost. It’s inevitable that a work which foregrounds the persistence of images in our consciousness, moved from print into cinema, to flicker like the mechanised dreams it depicts.

‘I do not believe that a dream should necessarily be taken for reality, or reality for madness.’

Words © Daniel Bennett

I suspect this influenced Auster also.

LikeLike

Yes, I suspect so. It has some of the Auster tropes: journeys, obsession, cinema, and an unsettling first person narrative. It’s all there…

LikeLike

Is Auster little more than the accumulation of his influences? I actually quite like a lot of his work: in particular the meditation on the death of his father. He does sometimes veer close to parody though.

LikeLike

I’m not really an expert on Auster, but he leaves me a bit cold. I loved The New York Trilogy when I first read it, but it turned out to be one of those books that didn’t stand up to re-reading. I tried The Book of Illusions, but found it flabby and unrewarding. An old friend of mine once said that everything was a little too perfect with Auster. The dead father, the time in Paris, the narrative games, the relationship with New York. If you were building a novelist you’d include them all, but does the whole really equal the sum of its parts? Not really, I think. The James Wood article on his work was pretty devastating, but pretty hard to disagree with.

LikeLike

this is actually very good… http://www.theguardian.com/books/2005/feb/05/fiction.paulauster

LikeLike

Thanks. Might be a good way to revisit that book…

LikeLike